Today, as the United Auto Workers begin their strike in a demand for a better livelihood, I am catapulted back to my childhood.

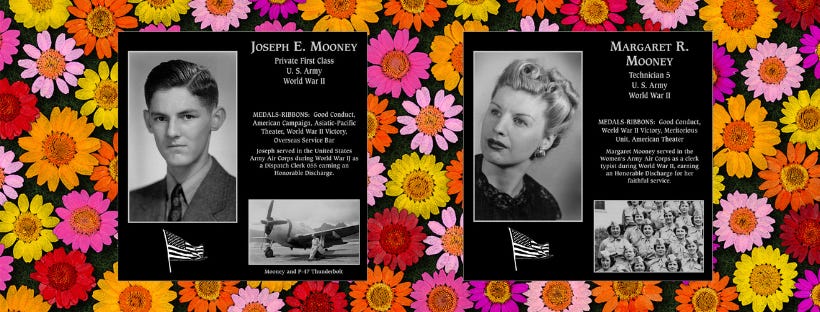

Detroit, “Motown,” is one of the cities where I grew up. Kansas City and Chicago were two others. No, I was not a military brat, although both of my parents did serve their country during World War II.

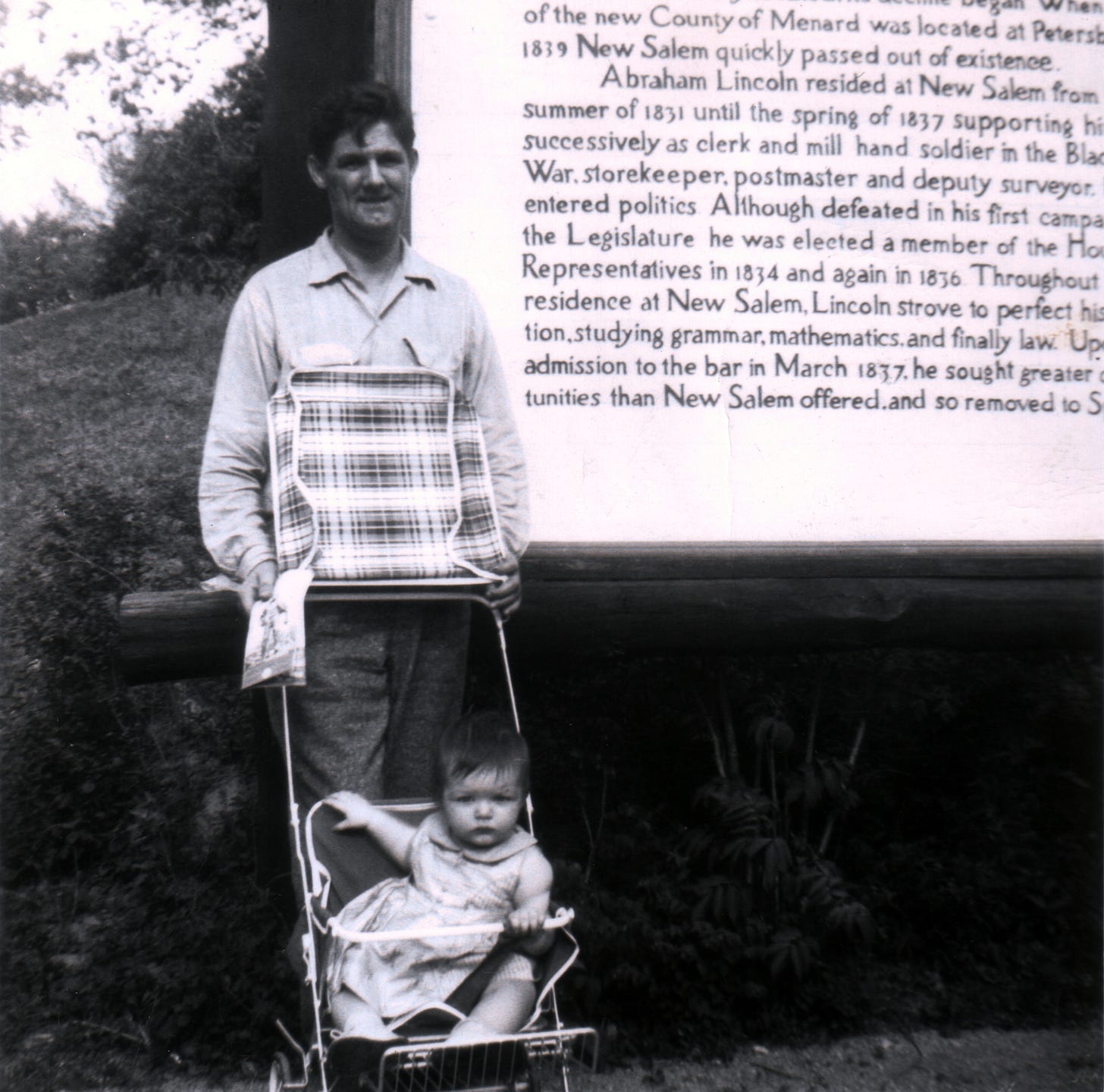

For 26 years, my father was a corporate sales manager for the Dodge Division of Chrysler. Ergo, everytime he got a raise, he’d also get a transfer. Both my parents were born and raised in Detroit. Right after he married my mother, he got his first transfer orders to Galesburg, Illinois, where I was born in 1955.

Galesburg, a small town located along the west side of the Mississippi River, was founded in 1837 by abolitionists who harbored escaped slaves and formed an underground railroad depot there during the Civil War. It was also the site of the great Lincoln-Douglas debate. And it was where the great American poet, Carl Sandburg, was born.

It’s intriguing to me that all the facts about my birthplace somehow affixed to my very DNA as I’m a poet myself who is passionate about human rights. There should be no place in our society for racism, sexism, ageism, or all the “isms” that form chasms between human beings.

My Catholic family continued to grow steadily as we migrated from Galesburg where Joe was born, to Chicago, where Jeanne and Tom were born. Then on to Kansas City, Kansas, where Marge and Rita were born.

Then Dad got papers for a transfer to Detroit. Mom and Dad were ecstatic about it, since it heralded a return to friends and family. But my five siblings and I were less enthusiastic. It was just another new place to start over again, and suffer the slings and arrows of being the “new kids on the block.” Again.

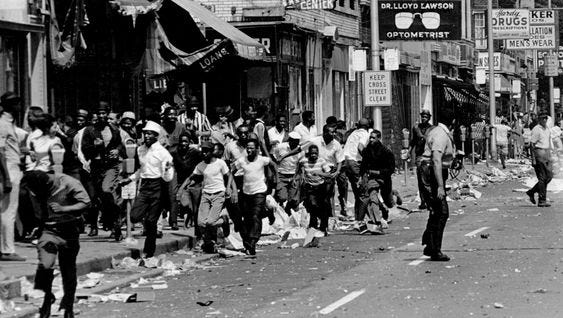

We arrived in St. Clair Shores, a lakeside community east of Detroit in 1967, the summer of the Detroit riots, and from our new neighborhood, we could see smoke curling in the skies to the west. This explosive unrest triggered the deep antipathy that some white folks in the city had for the folks of color and the whites began leaving in droves. Newspapers referred to it as the White Flight. Some of my cousins vacated town to move into suburbia or out of the state altogether.

Instead of reacting in fear, my mother and father dug their heels in. They both strongly believed in the resilience of the city. In the ensuing months, my mother began spending more time downtown to as she put it “create community.” I remember her coming home one day to announce she had paid a dollar for a HUD (Housing & Urban Development) home that she was going to rent out to some Catholic nuns she had befriended. She and these brilliant women began agitating for the right of women to become priests.

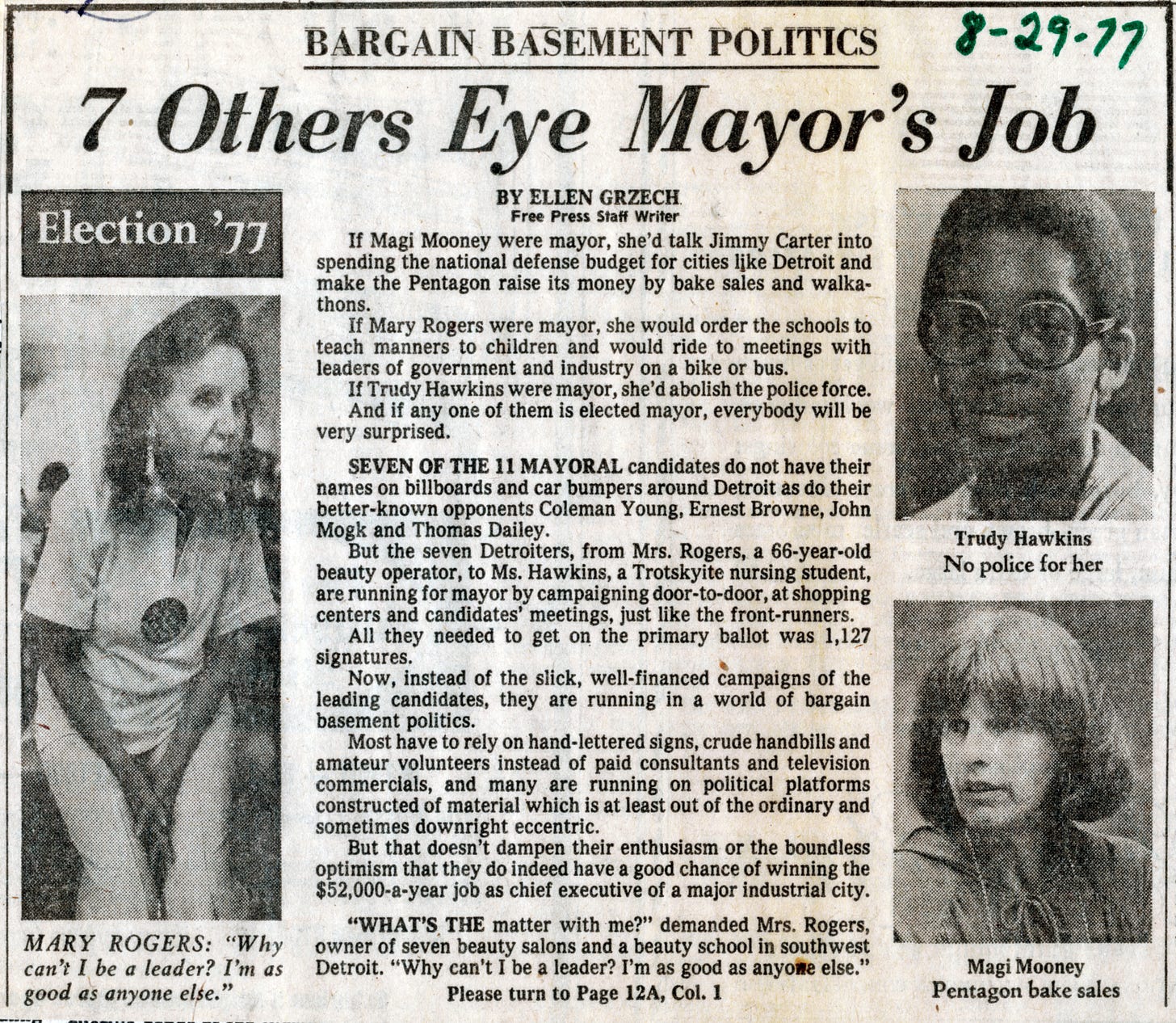

In the years following the riots, my mother slowly “retired from motherhood” and involved herself in local politics. In 1977, a decade after the riots, she ran for Mayor of Detroit. She garnered 1,151 votes. Incumbent, Coleman Young, Detroit’s first Afro-American mayor, won reelection in 1977.

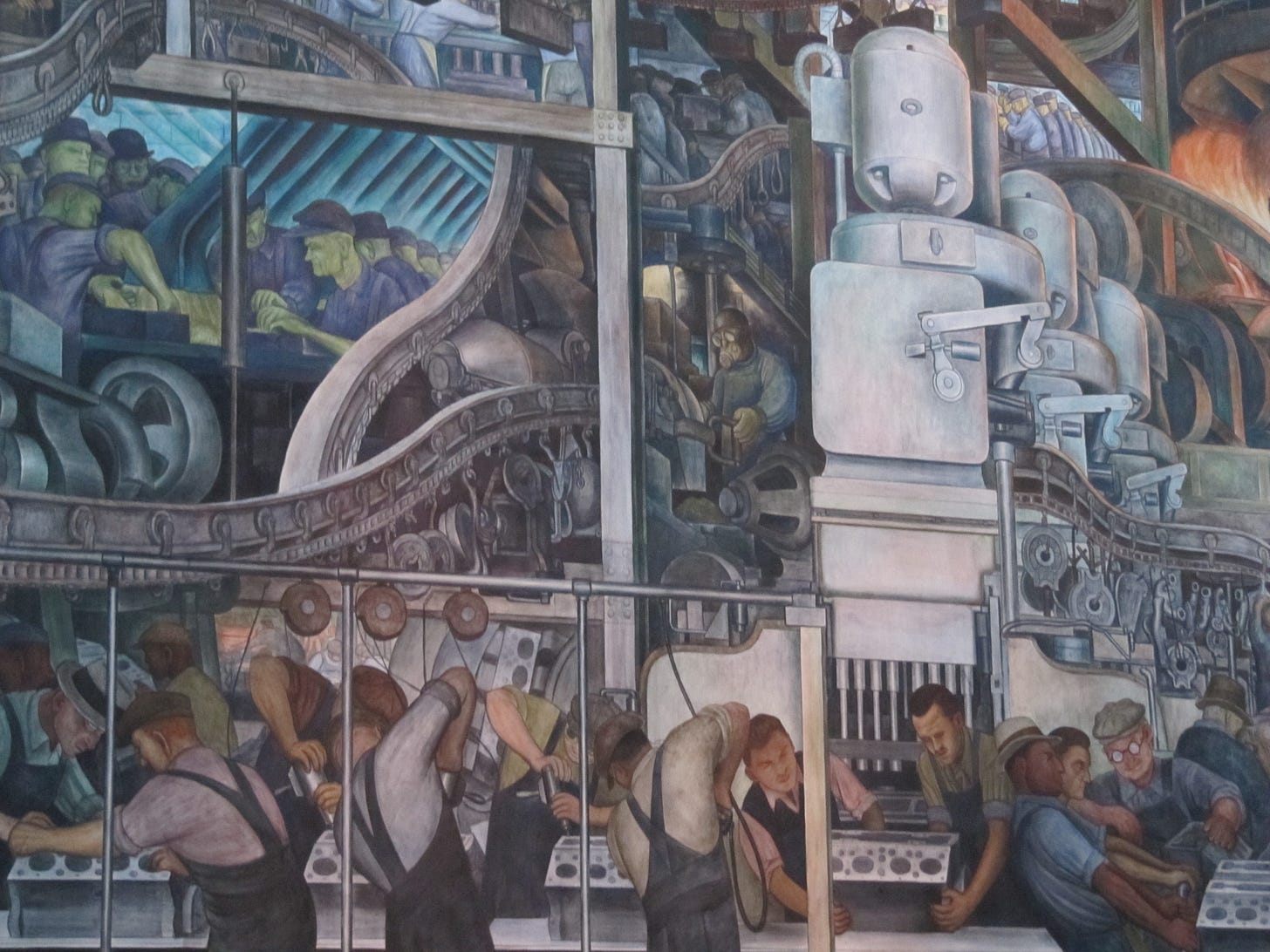

During my teen years, I became more acquainted with my family’s history. My dad’s parents had emigrated from Canada so Grandpa Mooney could work in the Ford auto factory.

It was the same with my mother’s parents. They, too, had emigrated to Detroit from a farm in Alpena, Michigan. Grandma Richard had paid off the farm by selling eggs and churned butter. After Grandpa gambled the farm away and took a ferry to Detroit in search of work in the auto industry, Grandma sullenly packed up the kids and what she could carry, following the husband she despised into Motown.

The Motown auto industry is the spine of my family history. Detroit called out with its promise of a pleasant and sustainable life.

One day I asked my father how he could keep selling more and more cars. Once people bought a car, wouldn’t that car last for a lifetime? That’s when Dad explained the concept of Planned Obsolescence.

And so we find ourselves today at a crossroad where workers are standing up to the billionaires whose profits pour in from exploiting their workers. Members of the auto industry, the movie industry and the transportation industry today have all committed to striking until they receive fair wages and benefits.

It occurs to me that billionaires who cling to their money suffer from some sort of malady. For them, money is alcohol. Money is a drug. For the rest of us, money is a currency and is meant to be circulated.

I think of my father who passed away in 2010, leaving among his effects, a shoebox full of veterinary bills incurred for a long line of beloved family dogs, a slightly-tattered golf sweater and a sweat-stained UAW baseball cap.

I love this so much. People should NEVER count Detroit OUT!

I'm crying so hard about the beauty of what your Dad cherished in his life, one of which I am certain was YOU!